July 8, 2025

On Tuesday morning, I was rudely awakened by the blaring sound of a screeching fire alarm. The drill drew us all out of our respective holes, like creatures emerging from their sleepy caves.

Gathering in the chapel, though, while the rising sun was shining through the stained glass window, made up for it!

After returning to my room and getting dressed for the day, I made my way back downstairs, where my group and I ventured to the Bodleian Library, because today, we were getting inducted.

The Bodleian Library is one of the oldest libraries in Europe, and home to over 3 million texts. From the website: “First opened to scholars in 1602, it incorporates an earlier library built by the University in the 15th century to house books donated by Humfrey, Duke of Gloucester. Since 1602 it has expanded, slowly at first but with increasing momentum over the last 150 years, to keep pace with the ever-growing accumulation of books, papers and other materials, but the core of the old buildings has remained intact.”

Among the miles and miles of treasures housed here, the Bodleian is home to incredible historic literary artifacts, such as the Gutenberg Bible, Shakespeare's First Folio, Tolkien's illustrations from The Hobbit, and Mary Shelley’s original manuscript of Frankenstein. It is a privilege to be one of the many students of Oxford who has access to these libraries, even if only for a short time.

We were escorted by two of the gatekeepers, who led us through much of the history and collective information for gathering resources and using the library for research.

There are many rules to using the Bodleian; so many that genuinely, I don’t remember all of them. However, there are some that are historically impacted and, in turn, incredibly interesting to note.

Duke Humphrey’s library is a non-lending library. King Charles I was denied permission to borrow a book back in the year 1645.

A copy of every book published in the UK is to be donated free of charge to the Bodleian collection. In 1610, Thomas Bodley entered an agreement with the Stationers’ Company of London and consequently named the Bodleian a legal deposit library.

Each reader is required to swear an oath before being allowed entry into the library.

The oath itself was instituted in the early 1600s by Thomas Bodley as well, assuring that the collection would stay maintained and well preserved. So, as a collective group, before being allowed in, we had swore the following oath together aloud:

“I hereby undertake not to remove from the Library, or to mark, deface, or injure in any way, any volume, document, or other object belonging to it or in its custody; not to bring into the Library or kindle therein any fire or flame, and not to smoke in the Library; and I promise to obey all the rules of the Library.”

After the oath, we were sworn as official Bodleian readers!

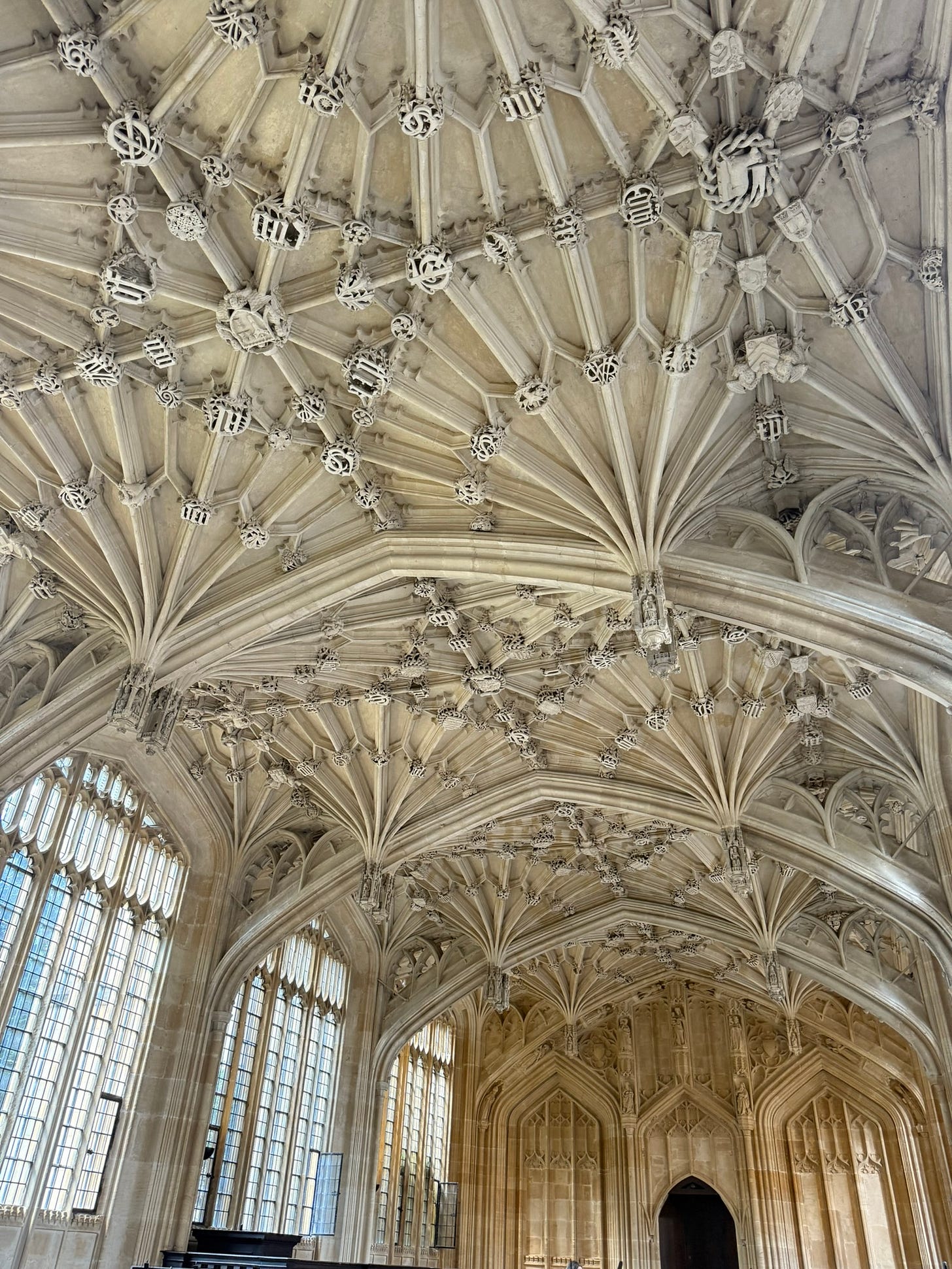

Once issued our cards, I decided to explore the grounds a little bit, and ventured into a room that was high on my list of things to see: the Divinity School.

The Divinity School is a medieval building built in the 1400s, and is the oldest teaching and examination room built in the Oxford complex. Its original Gothic architecture is absolutely stunning, and you may recognize it as the room used for the Infirmary of Hogwarts!

The room stands today as an event room which can be rented out (imagine getting married in here?!) but it also houses several very cool artifacts, including a chair built out of the broken pieces of Sir Francis Drake’s ship and donated to the Library in 1662; as well as a very intricately made metal chest with a locking mechanism that reminded me of Mad Eye Moody’s in the fourth Harry Potter, belonging to Sir Thomas Bodley himself.

I did a bit more wandering after, and ended up grabbing some lunch before returning to Exeter. I sat outside in the Fellow’s Garden and ate while reading up in preparation for my Jane Austen class.

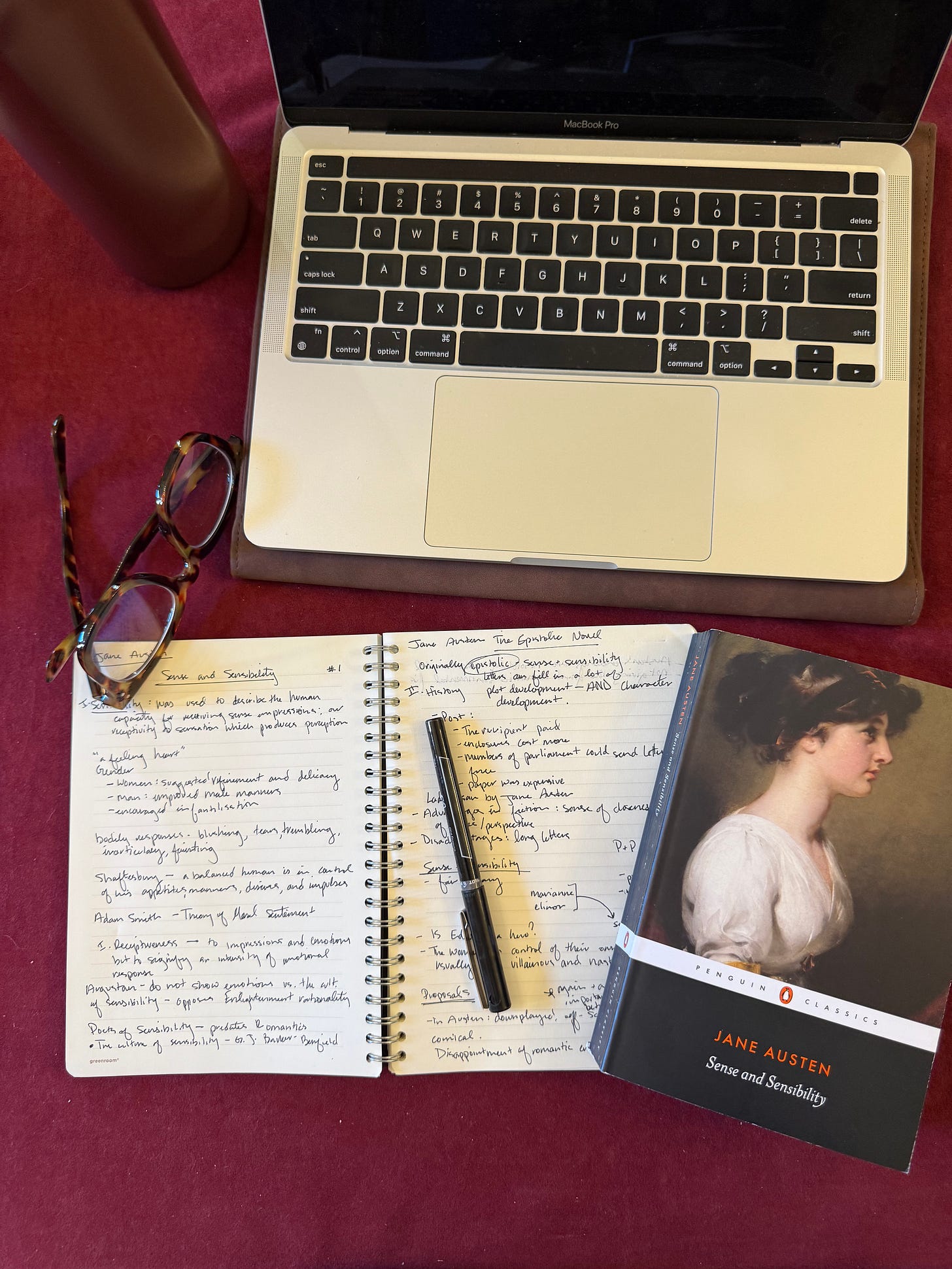

Class Notes

Sense and Sensibility was the topic of discussion for seminar #1. Sensibility is a way of describing the human capacity and reception to sensation, which produces perception. We discussed the ways in which sensibility depicted an intensity and a quickness of response, which was used in different ways for men and women. In women, sensibility more obviously suggested a kind of refinement and delicacy which invited a gentlewomanliness. In men, it is suggested that improved male manners and sensitivity are beneficial. Tears, blushing, trembling, and fainting were all signs of sensibility in men and women.

We discussed the history of sensibility—the Augustan age belief that showing emotions was considered improper, and the “cult” of sensibility, in contrast, as it opposes Enlightenment rationality. Poets of sensibility, predating Romantic poets, include Thomas Gray, Thomas Collins, and William Cowper, of whom Marianne Dashwood in the novel particularly loves.

The powerful sympathy and evoked emotion in such poetry is demonstrated in the sensibility of Marianne, who charges steadfastly into love, is the impulsive feeler compared to her sister Elinor’s grounded sense.

We talked a great deal about Edward Farris as a hero, which we all agreed he was not. In fact, it has become more and more obvious that, despite my previous understandings, Jane Austen is not a romantic writer, and would absolutely despise being called one at all.

Though the movies tend to accentuate the romances of the characters and the long-awaited proposal scenes, which we can all agree we absolutely adore and yearn for, and cheer for at the end, in her novels, proposals and weddings are extremely downplayed. More often than not, they happen off-page and are faintly comical. There is a sense of disappointment, perhaps, in readers who anticipate a fairytale ending with a show of romance. Austen knew that in order to sell her books, she had to include the endings that people wanted, but with a sense of reluctance did she put them in. There are even times of humor in which we are made to believe that Austen was perhaps poking fun at the subject.

More important to Austen, perhaps, is the relationship between females, and specifically sisters. But I don’t want to dive into that right now, because I want to write a much longer essay about that topic!

After class, I ended up striking up a conversation with my professor, and my friend Brittney and I decided to tag along with her for coffee before she was to give us a 4:30 pm lecture, once again on Jane Austen.

It is here, dear reader, that I tell you something which must be kept in confidence.

Upon walking out of Exeter, I passed a woman on the street with auburn hair, chaining her bike to a piece of scaffolding beneath a nail salon. This woman was Emma Watson.

I shan’t go into more details, because I have to appear chill and fun. But what an incredible thing it was to see her out in the wild!

She is more beautiful in person than I could have ever prepared myself for.

ANYWAY…

Our Austen lecture from Professor Sandie was a general overview of her life and her writing, which highlighted her irony, her metatextuality, her free indirect style, and the subversion of themes. Austen’s pragmatism regarding social conventions highlights the essence of the culture itself, which is that marriages and the roles of women were entirely pragmatic and mathematical. The law of primogeniture assured that an estate was not broken up through the division of heirs, as the eldest male in a family was to inherit. Women’s legal rights over their belongings and finances were subsumed under those of their husbands. Women could not even sell a piece of their own jewelry unless their husband approved, because it was legally not theirs to sell. And Austen comments on this subject a lot; we see the Dashwoods turned out of their family home after their father dies in Sense and Sensibility, for instance.

One last note of discussion: Austen began to discuss the idea of men who have earned rather than inherited their wealth. In Persuasion, Captain Wentworth is a self-made naval man, who is more of a hero than some of the other male heroes of her books. Anne Elliot, therefore, is more secure than other heroines by the end of the novel because of her independence and her security.

All so interesting!

I’m sure you’re tired of hearing me rattle on about Austen for today. After lecture, we had a lovely informal reception of drinks in the Fellow’s Garden waiting for us, and I was able to formally chat much longer again with Professor Sandie, who is a model of kindness, elegance, and knowledge. After wine, we had dinner, which consisted of sea bass, potatoes, and green beans.

After dinner, Anna and I took a walk, and found ourselves around Magdalen College, wandering an area neither of us had seen yet. I’m sure all of my female readers will understand when I say what an immense freedom and privilege it is to be able to walk around as a woman.

We came back to Exeter and I had a glass of wine in the courtyard while reading T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, and had a lovely visit from Walter the Exeter cat.

I’d say it was an incredible day, and I felt extremely lucky. What a joy it is to be here, alive, reading, with friends and adventures to spare! I’ll never not feel grateful for this experience.

Em